pinta-island-giant-tortoise-Chelonoidis-abingdonii-extinct-Lonesome-George

The Pinta Island tortoise is one of the giant Galápagos tortoise species

The Pinta Island tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdonii) belongs to the Galápagos tortoises: the species complex of Chelonoidis nigra comprises one of the two still extant giant tortoise populations on the planet – the other one being the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea), native to a remote atoll of the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean.

The common ancestors of the Galápagos tortoises arrived to the volcanic archipelago from mainland South America 2-3 million years ago, drifting 600 miles to the west with the Humboldt Currents. They colonized the oldest, easternmost islands of San Cristóbal and Espanola; then later they dispersed throughout the younger, westerly located islands of the archipelago – the process was probably parallel with and highly influenced by the continuing volcanic events and formation of the islands. They eventually inhabited 9 islands and developed into 14 variations – 11 islands and 16 variations, if we count the 2 disputed species of Rábida and Santa Fe Islands – that differ not only genetically but also in appearance and behavior.

critically-endangered-Galápagos-giant-tortoises

Most of the extant Galápagos tortoise populations are endangered

Due to massive exploitation mainly for their meat and oil by whalers and buccaneers in several waves from the 16th century, the numbers of tortoises declined from over 250 000 to around 3000 in the mid 1900s, when conservation programs were started to preserve and restore the rapidly demising unique ecosystem and wildlife of the archipelago.

The taxonomic status of the different Galápagos tortoise races hasn’t been fully resolved yet and the conservation status of the populations keeps also changing as continued research of the remaining wild and captive populations, DNA analysis and other modern scientific methods have revealed new information and surprising events in the last decades. Just in February this year (2019), a lonely female tortoise was discovered on Fernandina Island – a population (Chelonoidis phantasticus) that was originally known from a single specimen and thought to have gone extinct a century ago.

As of today, most of the 12 extant species (with at least one live purebred specimen) are assessed critically endangered or endangered, the 2 disputed species are surely extinct, and there are chances that two species – the Pinta and the Floreana (Chelonoidis nigra) populations – considered currently extinct may have unlocated live specimens or could be revived by interbreeding programs of hybrid specimens aimed to restore the approximate genetic constitution of these species.

Date of extinction: The Pinta Island tortoise was assumed to be extinct in the mid 20th century until 1 December 1971, when a lone male was found on the island. He was named Lonesome George and became a symbol for conservation efforts not only for the Galápagos tortoises but for all endangered species around the world. As despite all efforts no other individuals of his species were discovered either in the wild or in captive populations of the world’s zoos, with Lonesome George’s death on 24 June 2012 the species was thought to be extinct forever.

Lonesome-George-last-giant-pinta-tortoise

Lonesome George, the last known Pinta Island tortoise

©Copyright 3rdfloor / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

However, there’s still some hope for bringing back the Pinta Island tortoise from extinction once again. In 2008, an expedition of researchers reported that they found 17 young first-generation Pinta hybrids in the Volcano Wolf (Chelonoidis becki) tortoise population on Isabela Island. As Galápagos tortoises can have a lifespan of 100 years in the wild, the pure Pinta parent of these hybrid specimens could still be alive somewhere on Isabela Island.

Range: As its name suggests, the Pinta Island tortoise originally used to be endemic exclusively to Pinta Island (also known as Abingdoni Island), the northernmost major island of the Galápagos archipelago.

The most probable explanation for the presence of the Pinta hybrids on Isabela is that whalers and pirates regularly used to drop large numbers of tortoises – collected from other islands of the archipelago – in Banks Bay, near Isabela Island to lighten the burden of their ship. Apparently, many of these tortoises managed to get to the shore and survived; producing purebred specimens, and also hybrids by mating with the local Volcano Wolf population. This theory is supported by the fact that researchers have also found Floreana Island hybrids – the species was declared extinct in 1846 – in the same population.

Habitat: Pinta Island tortoises migrated seasonally up and down the volcano between two characteristic habitat zones of the island in response to changes in the availability and quality of the vegetation. In the dry season, they inhabited the meadows of the native Scalesia tree forest of the humid zone of higher elevations limited only to a small area of the island. In the wet season, they migrated to the warmer arid lowland zone that is primarily characterized by cacti, scattered deciduous trees, shrubs, herbs and xerophytic species; but turns into a grassy plain as the rain arrives. As tortoises used the same routes for many generations, the paths they’ve trodden into the undergrowth remained clearly recognizable even several decades after the last tortoises were seen on the island. This seasonal migration up and down the volcano is typical also to other Galápagos tortoise populations living on islands that are high enough to have a humid zone.

arid-zone-opuntia-forest-Galápagos-Santa-Cruz-Island

humid-highland-zone-Scalesia-forest-Galápagos-Santa-Cruz-Island

Opuntia forest in the lowland arid zone and meadow of the native Scalesia forest of the humid highland zone on Santa Cruz Island

©Copyright Dallas Krentzel / CC BY 2.0 and Andy Kraemer / CC BY-NC 2.0

The indigenous flora and fauna of most islands of the archipelago has suffered major losses and has undergone degradation during the centuries because of the invasive species introduced by humans. On Pinta, after releasing goats on the island in 1959, the native vegetation went through a long period of degradation as a consequence of the intense grazing pressure caused by the rapidly increasing feral goat population. During the 1970s, a complex conservation program was started to restore the original ecosystem of the island. The first step – the complete eradication of the feral goats – was achieved in 1999, resulting in Pinta being one of the islands with almost no exotic species. Fortunately the vegetation has been recovering rapidly since – without any loss in Pinta’s endemic plant species – but some indicators show that the biological diversity and the healthy structure of the habitat can’t be completely restored without the presence of the giant turtles.

Research shows that Galápagos tortoises are keystone species of their ecosystem, as they have a major impact on the structure and composition of the vegetation. They maintain open areas within forests and dense vegetation by grazing and by simply moving through their environment as minor bulldozers, thus – by thinning the understory vegetation and letting more sunlight in – they provide suitable habitat for many endemic plant species. They also play an important role in the dispersal and germination of seeds: they eat large amounts of plant matter that they deposit during their long distance migrations.

In 2010, 39 sterilized hybrid tortoises were released to Pinta to help to restore the ecosystem to its original condition before human’s arrival. Hopefully someday the conservation efforts to revive the Pinta Island tortoises will be successful and there will be a breeding population on the island again.

Description: Galápagos tortoises are the largest living terrestrial turtles, though their size varies across the islands/races significantly. Male individuals of the larger bodied species can reach up to 1.85 meter length and weigh over 400 kg, but the smallest one – native to Pinzón Island (Chelonoidis duncanensis) – measures only around 75 kg and 60 cm. Regarding its size, the Pinta Island tortoise was probably closer to the smaller end of the scale: Lonesome George weighed around 85-90 kg.

domed-shell-giant-Galápagos-tortoise-carapace-form

Galápagos tortoise with domed shell, the ancient carapace form characteristic to species from more humid islands

©Copyright Aki Sasaki / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The carapace morphology of the Galapagos tortoises is quite diverse, the species can be distinguished based on the shape and details of their shell. There are two main varieties: the domed shell – probably the original form of their ancestor – is characteristic for populations inhabiting larger islands with humid highlands where abundant vegetation is available easily near the ground all year; the saddleback form with proportionally longer necks and limbs is common in smaller islands where the arid zone is the main habitat, providing more limited resource of food in the dry season. The raised front opening of the carapace with the longer neck is thought to be an evolutionary response that enables the tortoise to extend its head up higher to reach the leaves and shoots of trees and cactus pads. Domed tortoises tend to be also larger in size than saddle-backed species. The Pinta Island population belonged to the saddle-backed variations: as Pinta is not high and large enough – maximum altitude is 777 meters, area 60 km2 – to have a fully developed, rich cloud forest of Scalesia; the island’s humid zone is rather limited in area and native tortoises had to adapt mainly to the limitations of the available vegetation in the arid zone.

saddleback-shell-giant-tortoise-Galápagos-carapace-form

Galápagos tortoise with saddleback shell, characteristic to populations from more arid islands like Pinta Island

©Copyright Andy Kraemer / CC BY-NC 2.0

Galápagos tortoises are herbivores; feeding huge amounts of grasses, leaves, cactus pads and every kind of fruits available. They have a very slow metabolism and are able to store significant amount of moisture and fat in their body and thus endure longer periods without water or food. Being cold-blooded animals, they adapt their daily routine to the ambient temperature of their environment. They bask 1-2 hours in the heat of the sun before they start their foraging tour; and in the hot season they have a ‘midday nap’ resting in the shade or half-submerged in muddy wallows trying to keep cool.

Galápagos-tortoises-resting-cooling-muddy-pool

Galápagos tortoises resting and cooling in a muddy pool

Galápagos tortoises mate primarily during the hot season – the process is quite cumbersome because of the huge, heavy shells – then females migrate to dry, sandy nesting areas to lay their eggs. The female tortoise prepares a nest by arduously digging a hole with her hind feet and seals the nest with a muddy plug above the hard-shelled, billiard ball sized eggs. For saddle-backed tortoises the average clutch size is 2-7 eggs, hatching after a four to eight months incubation period. Hatchlings measure only about 50 g and 6 cm; it can take several weeks for them to dig their way to the surface where they face severe hazards of the unfriendly environment. However, once they manage to survive the first 10-15 years, they grow big enough to have no natural predators and can easily live over 100 years.

At least that’s how it was before human’s arrival…since then, introduced feral rats, cats, dogs and pigs have been a constant threat to the eggs and young tortoises. On Pinzón Island, most of the hatchlings had been killed by rats for centuries until only about 200 old adults remained. In 2012, the invasive rodent population was eradicated and 2 years later the first newly hatched tortoises were reported from the island…

Cause of extinction: Ironically, the major cause of the demise of the Galápagos giant tortoises was their amazing adaptation that once helped their ancestor to reach the archipelago on the currents and colonize the islands – the ability to survive without water of food for up to a year. From the discovery of the archipelago in the 16th century, whalers, fur hunters and pirates frequently used it as a base for restocking; taking hundreds of tortoises on board as living meet and water supplies for their long journeys. Exploitation increased in several waves during the centuries; in addition, the original ecosystem of the archipelago also had to face the usual threats islands experience with human invasion: introduction of alien predators (rats, cats, dogs, pigs), grazing competition (goats, cattle), and the degradation and loss of habitat caused by the growing agricultural activity.

endangered-Galápagos-giant-tortoise-migrating

Hopefully the still extant Galápagos tortoise populations will HAVE a future…

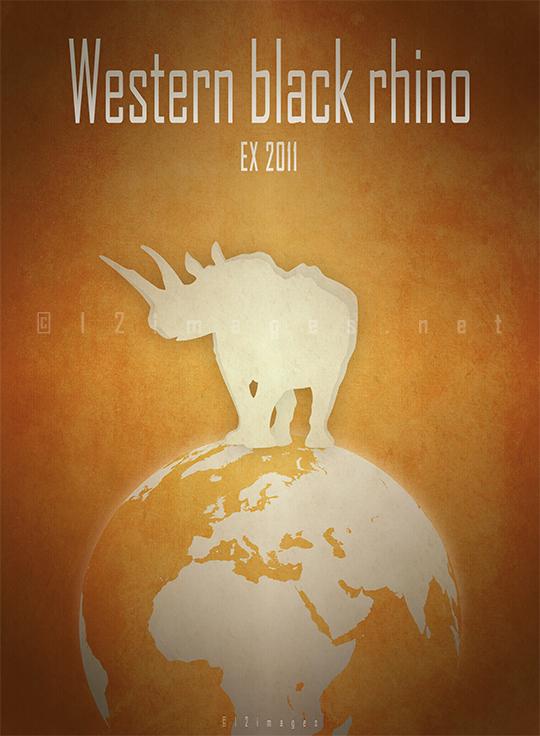

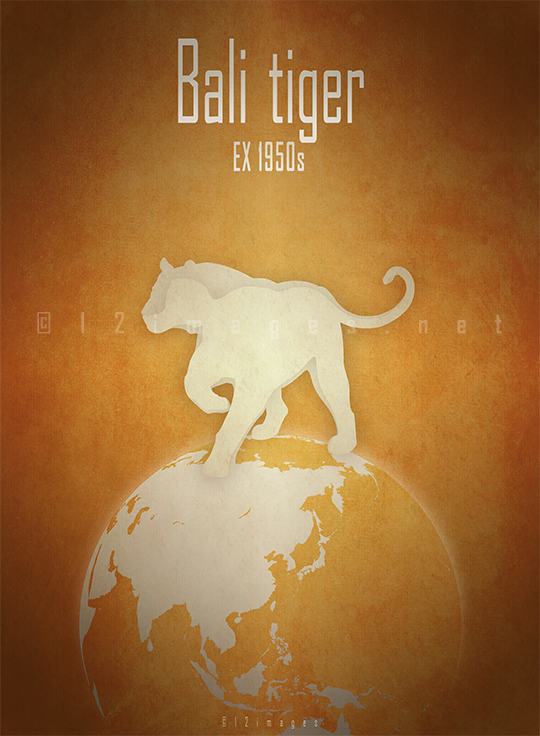

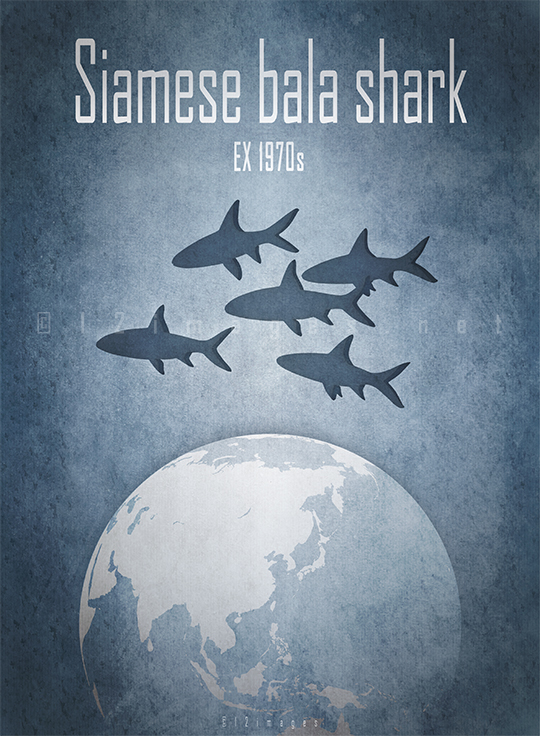

The Pinta Island tortoise poster at the top of this post is available in my store on Redbubble, with design variations more suitable for apparel and other products. My whole profit goes to the Sea Shepherd to support their fight to protect our oceans and marine wildlife.